How Can We Preserve the Character of Space? An Interview with the Saudi Ethnographic Diary

The Saudi Ethnographic Diary is an initiative on social media. It is managed by three interdisciplinary Saudi practitioners, hailing from diverse social backgrounds. Asaad is a visual artist and physician. He was born in Medina to a family with Turkish, Syrian, and Egyptian roots. His family most likely migrated to and settled in Medina, near the Prophet’s Mosque, during the Ottoman rule, where his ancestors worked in facilitating services for hajj and umrah performers. Anhar is a contemporary artist and filmmaker from an Indonesian-Yemeni background. Her family migrated to Jeddah in the 1970s, and they mainly worked in trade and photography. Lastly, Lena is a physician interested in urban voices and social anthropology. She was born and raised in Jeddah. She’s also a fourth-generation daughter to a Makkah-based family with West African roots. Her great grandfather migrated to Makkah, during the ending of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, seeking an education in sharia. The Diary’s fourth member is the audience who engaged with it since its launch. Regardless of their audience’s diverse backgrounds, they aren’t that different from the three founding memembers when it comes to their interdisciplinary practices and interests.

How and when did the Diary start?

We started in 2017. The first spark was ignited when Asaad, who was born and raised in Medina, realized that the place he grew up in was rapidly changing. Many places he used to frequent as a child, such as the markets and neighborhoods near the Prophet’s Mosque, vanished. This was mainly due to developing and expanding efforts at the Mosque. He felt nostalgic to the markets he visited with his grandmother, reminiscing about the house (located near Bir Bida’ah) his father was born in and told him a lot about. The house was removed before Asaad was born, making it an extension of the Mosque. This deeply impacted Asaad, who mourned all the lost pre-modern architecture in Medina.

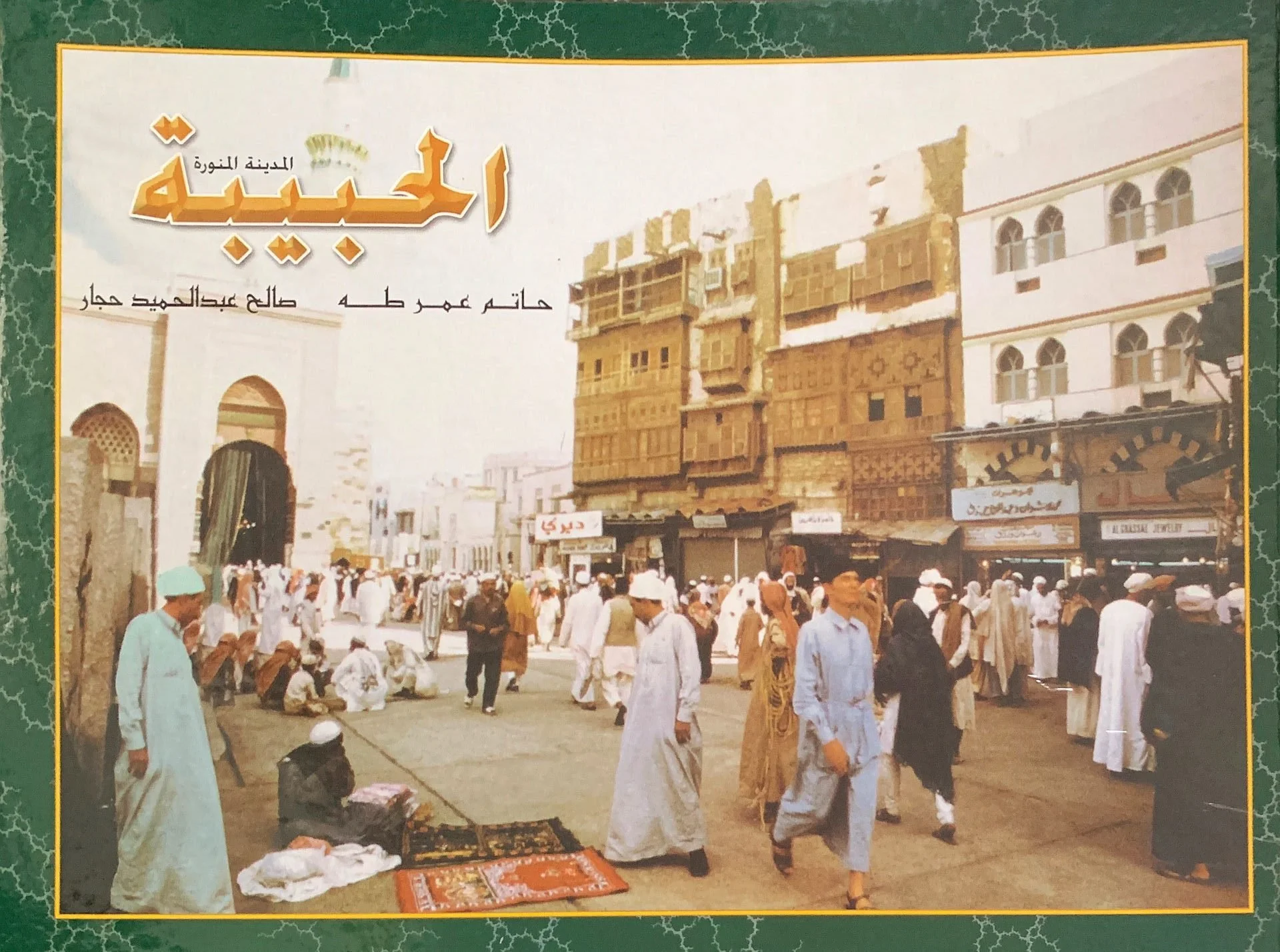

His family owned a copy of Alhabiba by Hatem Omar Taha and Saleh Abdulhamid Hajjar (1998), which contains photographs of various neighborhoods in Medina before the Mosque’s expansion. It was difficult for Asaad to accept that all of them are gone now. It simultaneously made him aware of the importance of documentation and motivated him to explore photography. He made his short film about Medina, Nonself-Portait (2019), which was later screened at Tajreeb, one of the programs at the first edition of the Red Sea International Film Festival. These observations and projects marked the beginning of the Diary.

Alhabiba cover by Hatem Omar Taha and Saleh Abdulhamid Hajjar

Why has the “character of space” become the main pillar in the Diary?

Perhaps our connection to space and its change present a form of inseparable duality. Moreover, the character or nature of space pushes us to wonder about its substance, history, layers, and our awareness of it, especially as it intersects with our physical proximity to those we share space with. In short, we’re asking: what are the behaviors produced here, and how can we detect and locate them?

Besides tangible changes in architecture and cities’ reformations, we’re in the midst of fast and complex changes on social and demographic levels in Saudi. The changes revolve mainly about the living and working conditions of migrants, the systems behind kafala and residency, and the Saudi nationalization of employment policies (Saudization). These changes remain invisible, and so are their consequences. Hence, we decided, especially at the beginning of our journey, that it was crucial to raise awareness and make these changes visible by documenting them.

What methods and approaches did the Diary utilize or innovate to preserve the character of space?

Through traditional methods that are rooted in curiosity and self-introspection. This includes documenting the changes our different regions are experiencing in visual, auditory, and written formats. However, our approach transformed after we launched a call for submissions in response to the removal of neighborhoods in Jeddah (October 2021). This turned our approach to a collective one, making our audience the fourth member of our team and enabling them to actively contribute to and engage with it. They taught us about alternative methods and platforms to make change visible, including YouTube and Snapchat.

How can we contribute to the Diary?

The Diary accepts submission (including anonymous submissions) from all over the Kingdom via its Instagram account or email. We ask some questions about the submission, including the picture’s location and its importance to the contributor and their community. We eventually post the picture on our account with our audience.

The Diary shares and posts about cultural events, as well as calls for submissions catered to researchers and archiving enthusiasts. We also help and promote shops that have been moved to other neighborhoods. Most importantly, the Diary encourages its audience to observe, research, and investigate.

The Diary accepts and posts contributions of different neighborhoods and cities in Kingdom on their Instagram account

How many cities and neighborhoods did the Diary cover? What have you learned about them, and are there any patterns you observed?

The Diary primarily covered three cities (Jeddah, Medina, and Makkah) and almost 23 neighborhoods. Our coverage taught us many individual and collective lessons, the first being a new understanding of space, what it’s made of, and how we document it. Archiving is almost a never ending labor. With every photograph or new medium we explore, we realize and learn about an entirely different approach, creating endless opportunities made possible by cellphones, social media, and the urge to capture the moment. This process started many conversations and questions about the politics and anthropology of space, the ethics of archiving it, and general aesthetics.

We definitely observed different patterns, not by documenting necessarily, but through receiving and categorizing the submissions. Some neighborhoods tend to document social events, including weddings, farewell gatherings, football matches, and Ramadan feasts. Others document restaurants, shops, and markets. We also noticed that each neighborhood had a center, like courtyards, markets, mosques, and the houses of the neighborhoods’ elite.

We also noticed differences in ethnicities and tribes represented there, as well as patterns of internal migration. This is accompanied by certain architectural touches. For example, in Jeddah, the presence of East African residents around Sudanese cafes and restaurants in Al-Hindawiya and Enakish districts caught our attention. In Al-Hindawiya, we also noticed how the Souq alyomanah market extended from the heart of Harat al yamaniyah (The Yemen Quarter) to the front of 60th Street. In As Sahifah district, we were fascinated by As Sahifah Mall, a shopping center specializing in all the needs of Somali residents, ranging from a bilingual religious bookstore on its 2nd floor to a selection of restaurants on its last floor. Moreover, Al Kandarah was an open market filled with urban houses that hosted the hadharem and their trade. The tribes of Juhayna and Harb mostly resided in parts of Al Jami’ah district, where many neighborhoods and mosques were named after their sheikhs. The identity of these parts changed as talented football players emerged. Finally, we noticed that pattern in Jeddah’s Quwayzah and Al-Rawabi districts’ neighborhoods, where most of their names were influenced by the movement of tribes there for over three generations.

The Diary accepts and posts contributions of different neighborhoods and cities in Kingdom on their Instagram account